Experiment 14

Introduction

Our final post in the Quantum Smalltalk series explores a thought experiment proposed by Avshalom Elitzur and Lev Vaidman to demonstrate an unusual quantum feature - interaction-free measurement.

Experiment #14

Elitzur and Vaidman proposed the following thought experiment:

You are given 100 EV bombs. Due to a manufacturing problem that was caught too late, some of the triggers are defective. Your job is to try to salvage as many good bombs as possible.

What is an EV Bomb?

This experiment requires us to add a new piece of equipment to our workbench - the EV bomb. This bomb is special because it has a very sensitive trigger: a photon detector. Turn out the lights now because a single photon can cause this bomb to explode!

The following rules describe an EV bomb:

- If the trigger is not defective, when a photon enters trigger tube the bomb explodes and you cannot salvage the bomb.

- If the trigger is defective, when a photon enters the trigger tube the bomb does not explode and the photon continues undisturbed out the trigger tube exit.

- The distance from the bomb to the rest of the equipment is sufficiently large to protect the equipment; only the bomb is destroyed if an explosion occurs.

Attempt #1

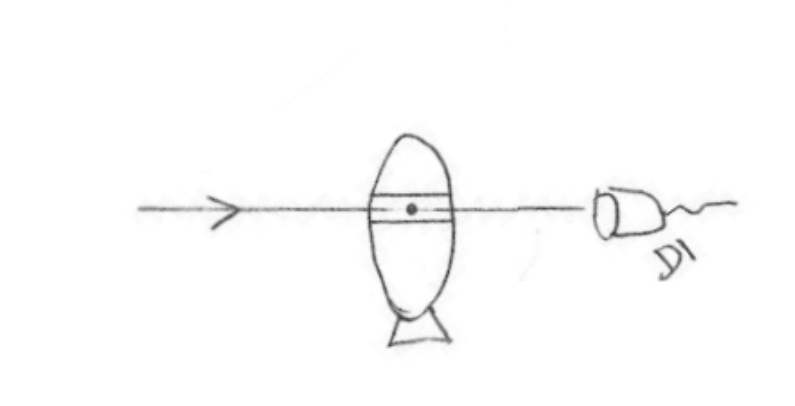

Our first attempt to salvage the good EV bombs isn’t very clever. Let’s just shoot some photons at it and see what happens.

| Count | Explosion | Photon detected at D1 | Bombs salvaged |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | Yes | No | 0 |

| 20 | No | Yes | N/A |

We tested all the bombs and determined with 100% accuracy which ones were defective and which ones were good. However, we failed to salvage any of the good bombs because they were blown up in the process. If it seems like this thought experiment has no solution, then you are likely restricting yourself to solutions that follow the principle of locality. (For extra details on locality see Appendix B & C below.)

Attempt #2

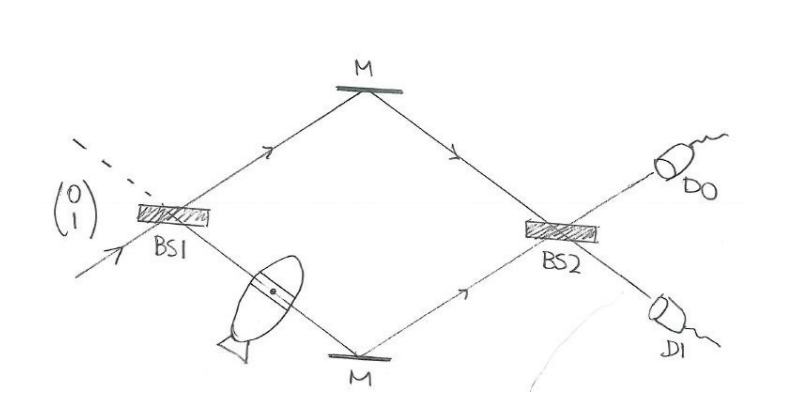

Our second attempt should look familiar by now - the Mach-Zehnder setup. We place the bomb on the path between the first beamsplitter and the lower mirror and observe the following results:

| Count | Explosion | Photon detected at D0 | Photon detected at D1 | Bombs salvaged |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Yes | No | No | ? |

| 40 | No | Yes | No | ? |

| 20 | No | No | Yes | ? |

Clearly we can’t salvage any of the 40 good bombs that blew up. But what about the remaining 60 that didn’t explode? Were they all defective? To answer this question, let’s look at our simulation output. We first observe what happens to photons that pass through a defective EV bomb:

Emitting a photon from lower path. >> #(0 1)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon passes through defective EV Bomb placed on the lower path. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon bouncing off of a mirror. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.9999999999999996 0.0)

Photon finally detected with following probabilities: >> #(0.9999999999999996 0.0 )

Defective EV bombs act as if they aren’t there (just like Experiment #11) so there is a 100% chance that it will be detected at D0. Good EV bombs give a different result:

Emitting a photon from lower path. >> #(0 1)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon detonates EV Bomb on the lower path with 50% probability. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0)

Photon bouncing off of a mirror. >> #(0.0 0.4999999999999999)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.2499999999999999 0.2499999999999999)

Photon finally detected with following probabilities: >> #(0.2499999999999999 0.2499999999999999)

From the simulation we see that half of the time the EV bomb detonates. Therefore, we can deduce that there were 80 good bombs (because we observed 40 detonating) and 20 bad bombs (the remainder). The output probability for the bombs that don’t detonate is 25% at D0 and 25% at D1. This means that the 20 bombs we observed at D1 are good! The other 40 bombs that didn’t detonate and that we observed at D0 have a 50% probability of being good, but we can’t tell which is which.

| Count | Explosion | Photon detected at D0 | Photon detected at D1 | Bombs salvaged |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Yes | No | No | 0 |

| 40 | No | Yes | No | 0 |

| 20 | No | No | Yes | 20 |

Attempt #3 (optional)

It’s a shame that we were only able to recover 25% of the good bombs. We can achieve the theoretical limit of 50% (or 40 in our example) by using something called the Quantum Zeno Effect. The details of how to extend our setup using this effect are left up to the reader. I recommend this video.

Interaction-free measurement

The EV bomb experiment demonstrates a non-local feature of quantum mechanics; we were able to learn something about a path that the photon didn’t take. Furthermore, we did so without any prior information. This is called an interaction-free measurement.

This is in contrast to, for example, the case where it is known that an object is located in one of two boxes. Looking and not finding it in one box tells us that the object is located inside the other box. This is also an interaction-free measurement, but it does not violate non-locality because we used prior information.

Summary

Experiment #14 presented another weird quantum feature of interaction-free measurements. Although our treatment was theoretical, know that these results have been duplicated in the lab.

Conclusion

This post concludes the Quantum Smalltalk series. I am amazed at how much of the quantum world we were able to explore using the Mach-Zehnder setup. I hope that these posts piqued your interest in quantum mechanics. There are a lot of great resources available. As a next step, I recommend the book Through Two Doors at Once: The Elegant Experiment That Captures the Enigma of Our Quantum Reality by Anil Ananthaswamy. Alternatively, if you find general relativity generally fascinating then you might want to explore more advanced topics like the black hole information paradox.

Appendix A: The Smalltalk code

The full Pharo package can be found at dlfeps/MZI.

Appendix B: Einstein and locality

The principle of locality states that for one point to have an effect one another point, something must travel between the points to cause the effect. The special theory of relativity limits the speed of travel to the speed of light. Therefore an event at point A cannot cause a result at point B in a time less than D/c, where D is the distance between the points and c is the speed of light in vacuum.

Einstein believed in locality. In one of his 1935 papers, Einstein (along with co-authors Podolsky and Rosen) describe a thought experiment that demonstrates a scenario where quantum mechanics violates locality and concluded that quantum theory does not provide a complete description of reality. The paper ends by saying:

“While we have thus shown that the wave function does not provide a complete description of the physical reality, we left open the question of whether or not such a description exists. We believe, however, that such a theory is possible.”

Einstein believed that the solution to the paradox lay in introducing additional (possibly inaccessible) variables. Such a theory is known as a hidden variable theory.

Appendix C: Bell and locality

Almost 30 years after Einstein’s paper, John Stewart Bell proposed a theory that states that no theory of hidden local variables can ever reproduce all the predictions of quantum mechanics. To date, all such experiments have supported the theory of quantum physics and not the hypothesis of local hidden variables. The 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to three scientists (John Clauser, Alain Aspect, and Anton Zeilinger) for their efforts to experimentally validate violations of the Bell inequalities. Bell’s test proves that quantum mechanics is either non-local itself or has non-local hidden variables.