Experiment 15

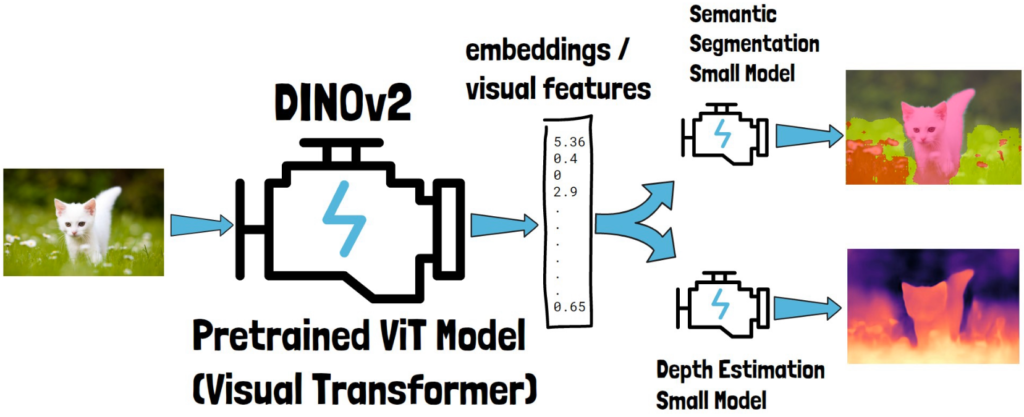

This post explores DINOv2 - a foundational vision model from FAIR.

Introduction

Yann LeCun is one of the godfathers of deep learning1. He believes that one of the most critical challenges to solve in the current era is how to give AI systems common sense. Common sense is difficult to define, but I believe that it keeps me alive and allows me to learn new skills helps with relatively few attempts (compared to deep learning). LeCun calls this elusive knowledge the dark matter of AI.

How do we impart this knowledge to our AI systems? LeCun believes the solution lies in self-supervised learning. Self-supervised learning is a technique that adapts tasks that conventionally require labels into an unsupervised learning task (e.g. next word prediction). Self-supervised learning tasks can take advantage of massive amounts of data. If designed properly, the model will learn accurate, meaningful representations of the data. Large Language Models have been popular in the news lately due to their uncanny ability to achieve human-level performance on many tasks. Their sucess is due, in part, to their ability to leverage large amounts of unnannotated text through self-supervised learning.

It is no surprise that the most successful self-supervised computer vision models come from LeCun’s lab (Fundamental AI Research team at Meta). They published DINO (2021) and DINOv2 (2023) as foundational image models. Foundational models are meant to serve as a resusable backbone for many tasks.

Image retrieval

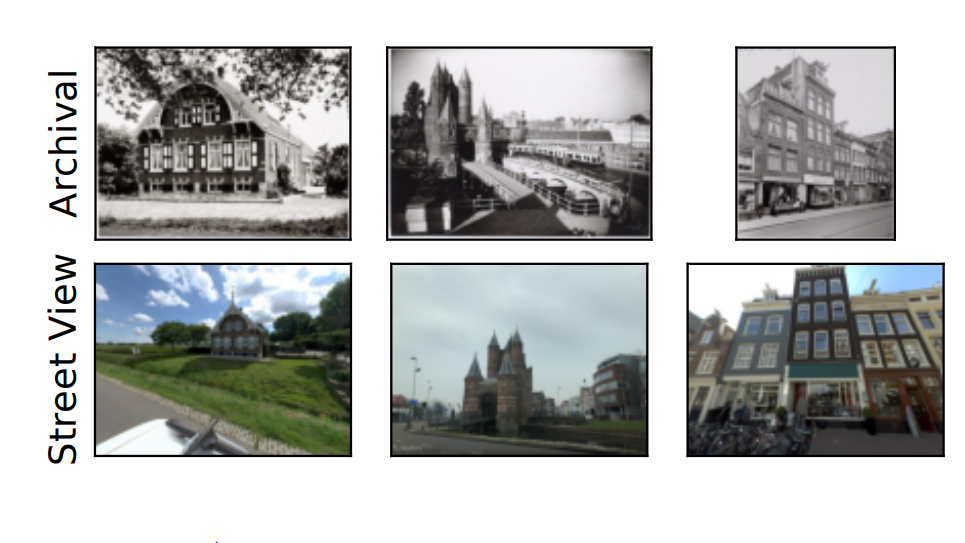

In their paper, DINOv2 is benchmarked against many SOTA computer vision tasks. One of those tasks is image retrieval. Image retrieval uses images to search for other relevant images. It can help users discover new images guided by visual similarity. Popular benchmarks for image retrieval methods include the Oxford building and Google Landmarks. In this post I wanted to explore a dataset that was designed to retrieve images through time - the AmsterTime dataset.

AmsterTime dataset

The AmsterTime dataset offers a collection of 2,500 well-curated images matching the same scene from a street view matched to historical archival image data from Amsterdam city. This is a challenging dataset for image retrieval because the query and gallery sets were taken many years apart so there is often structural changes for the same location.

Image retrieval with DINOv2

Finding similar images with DINOv2 is simple. First, compute the embedding vector for each image in the gallery by passing it through the DINOv2 model. Then, given a query image, compare its embedding vector with those from the gallery using cosine similarity:

The embedding vector

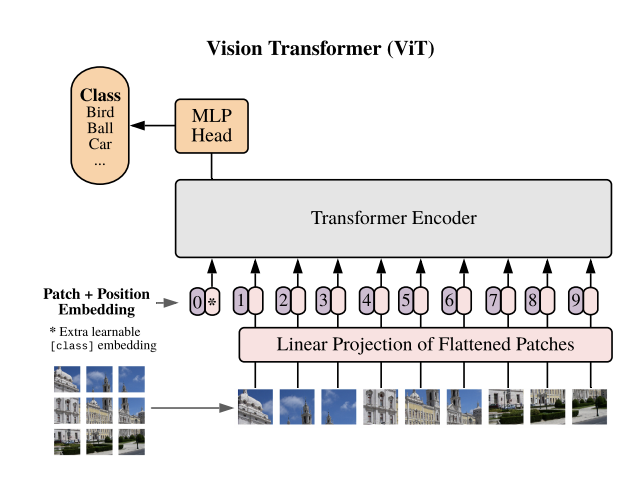

DINOv2 is a vision transformer model. As such, it transforms an image into patches and processes those patches a sequence of patches.

The sequence is processed by the model and the embedding vector referenced here refers to the [CLS] token of the final layer (represented by the “*” in the figure above). Since the [CLS] token does not represent an actual token, the transformer learns to encode a general representation of the entire image into that token. One of the most desirable features of DINOv2 is that the attention maps associated with the [CLS] token of the last layer tend to be aligned with salient foreground objects (i.e. the model is attending to the primary subject of the image). It is worth looking at the code to see how to extract the [CLS] token:

def get_cls_token_for_images(images, processor, model):

collect = []

for i in tqdm(images):

inputs = processor(images=i, return_tensors="pt")

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs)

last_hidden_states = outputs.last_hidden_state

collect.append(last_hidden_states[:,0,:]) # cls token

return torch.cat(collect)

Results

A common metric for reporting results in image retrieval is Recall@N. Here are the results for the AmsterTime dataset:

| query | gallery | recall@1 | recall@5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmsterTime | archival | streetview | 0.43 | 0.68 |

Not bad considering the difficulty of the dataset. This means that 43% of the time the top matching image is the correct one. Let’s look at some of the cases where this worked well (query image on left, correct result from gallery on right).

It is also informative to look at the cases where the approach failed. Below are the top-10 worst performing queries (largest distances between query and gallery). Each row contains the query image, the top predicted result, and finally the correct result.

We see that many of the correct results contain occlusions or severe camera distortions, preventing the structural features of the building from being matched. In most of the cases, it is difficult for even a human to match the images.

Since the AmsterTime dataset contains pairs of images across time (1250 archival, 1250 streetview) we can also reverse the gallery and query sets. Surprisingly, its easier to predict the future than the past ;)

| query | gallery | recall@1 | recall@5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmsterTime | archival | streetview | 0.43 | 0.68 |

| AmsterTime | streetview | archival | 0.35 | 0.57 |

Conclusion

This post demonstrated the potential power of the DINOv2 foundational vision model. The results show that the model is capable of capturing the salient information in an image retrieval task without any prior training. The code for this experiment can be found at my ML portfolio website.

Footnotes

-

Yoshua Bengio and Geoffrey Hinton are also given this title. In 2018 LeCun, Bengio, and Hinton won the Turing award for their contributions in deep learing. ↩