Experiment 12

Introduction

Experiment #12 doesn’t introduce any new concepts, but it prepares us for a surprising result in Experiment #13.

Experiment #12

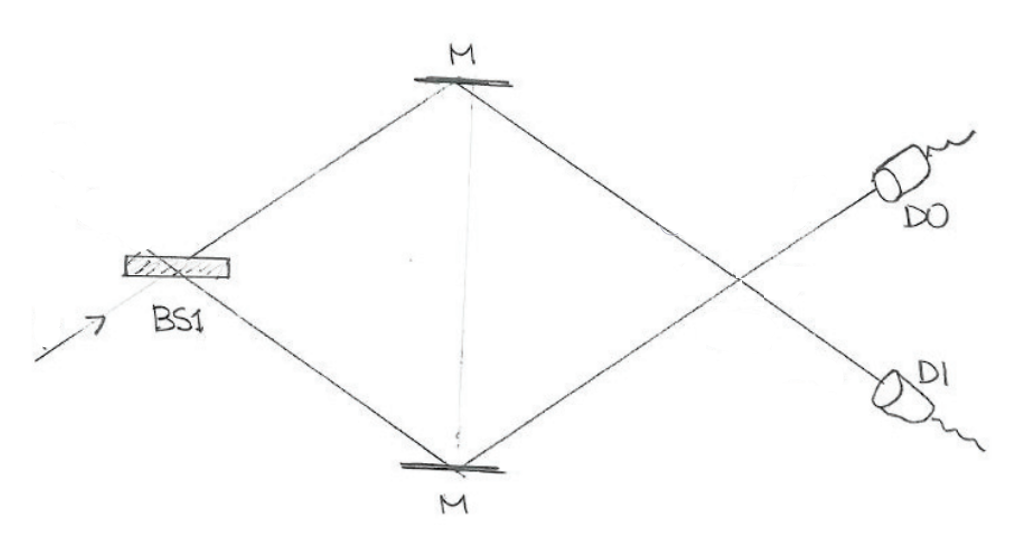

Modify the setup from Experiment #11 by removing the second beamsplitter. This allows the photon to take one of two paths:

| State name | Path at BS1 | Detector | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | Reflected | D0 | ? |

| T | Transmitted | D1 | ? |

We don’t yet know the outcome of the experiment, but based on our observations from Experiment 10 we might expect an equal distribution between D0 and D1. Let’s run the Smalltalk simulation.

Emitting a photon from lower path. >> #(0 1)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon bouncing off of a mirror. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon finally detected with following probabilities: >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Our intuition was correct! After the first beamsplitter the photon is equally likely to be on the upper and lower path, but this time the paths are not recombined using the second beamsplitter. So any photons that are reflected at BS1 end up at D0 and any photons that are transmitted at BS1 end up at D1. We always know which path the photon took.

The wavefunction

How does this affect the photon’s wavefunction? Initially, after interacting with the beamsplitter we do not know which path the photon is on. Therefore its wavefunction is a superposition of states of the upper and lower paths. At the moment just before the photon would reach D0 or D1, its wavefunction predicts with 50% probability that the photon will be detected at D0 and 50% probability that the photon will be detected at D1. An instant later it is detected at either D0 or D1. But how does the wavefunction predict two equally likely locations in one instant and then the next instant, the probabilities are gone and the photon is detected at D0 or D1?

Measurement of a quantum system

When scientists say they are taking a “measurement” they are describing the action or process of observing something in order to gain information. But in quantum mechanics, the term “measurement” has both practical and philosophical implications. From a practical point of view, measuring a quantum system changes the quantum state that describes that system; this is sometimes described as causing the wavefunction to collapse (i.e. it is no longer in a superposition of states). From a philosophical point of view, how did the system know it was being measured? In other words, what caused the collapse? How are the probabilities converted into an actual, well-defined classical outcome? The answer to these questions depends on your interpretation of quantum mechanics and is beyond the scope of this post. For those interested, I thoroughly enjoyed listening to this panel discussion on the topic.

Summary

Experiment 12 explored the measurement problem - the instant that the photon becomes a particle (as described by the wavefunction). The next experiment challenges our everyday understanding of reality.

Appendix: The Smalltalk code

The full Pharo package can be found at dlfeps/MZI.