Experiment 11

Introduction

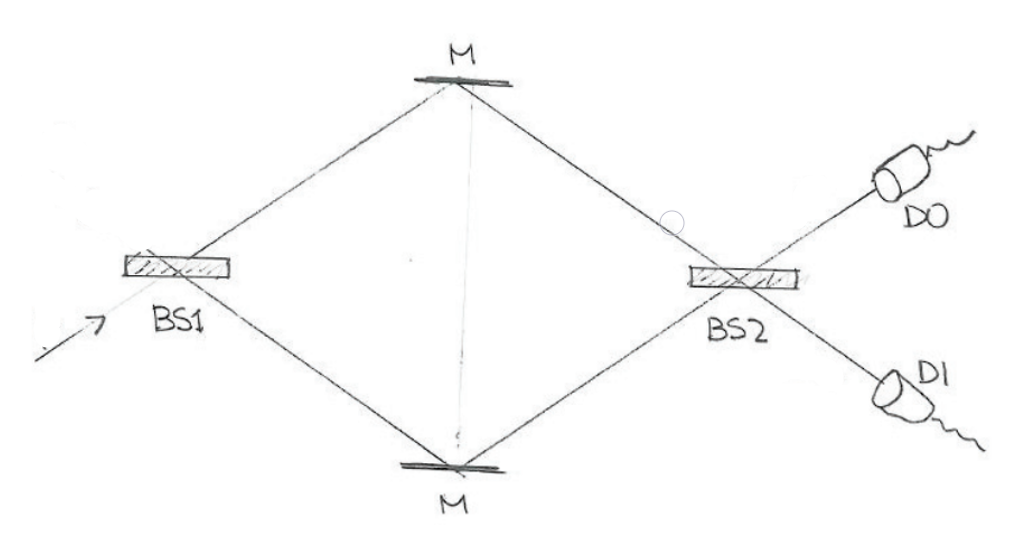

Experiment 11 introduces the concepts of quantum superposition by making a slight modification to Experiment 10.

Experiment #11

Modify the setup from Experiment #10 by removing the block on the lower path. This allows the photon to now take one of four paths:

| State name | Path at BS1 | Path at BS2 | Detector | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | Reflected | Reflected | D1 | ? |

| RT | Reflected | Transmitted | D0 | ? |

| TR | Transmitted | Reflected | D0 | ? |

| TT | Transmitted | Transmitted | D1 | ? |

We don’t yet know the outcome of the experiment, but based on our observations from Experiment 10 we might expect an equal distribution between D0 and D1. However, that is not what we observe. Let’s run the Smalltalk simulation.

Emitting a photon from lower path. >> #(0 1)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon bouncing off of a mirror. >> #(0.4999999999999999 0.4999999999999999)

Photon passing through a beam splitter. >> #(0.9999999999999996 0.0)

Photon finally detected with following probabilities: >> #(0.9999999999999996 0.0)

After the first beamsplitter the photon is equally likely to be on the upper and lower path (i.e. 50/50) - the same as in Experiment 10. But this time the lower path is not blocked and the second beam splitter sends all of the photons to D0. How is this possible?

WHAT is Superposition

Quantum mechanics explains this phenomenon by saying that the wavefunction of the photon was in a superposition of two states (i.e. one state going through the upper path and one state going through the lower path). NOTE: this is different that saying that it went through both paths or neither path.

The experiment was designed in such a way that the wavefunction for state RR lags behind state TT by half a wavelength, resulting in destructive interference. The probability amplitude goes to zero and there are no photons at D1. States described by RT and TR arrive with their waves in sync, resulting in constructive interference. The probability amplitude doubles and all the light reaches D0.

The photon itself doesn’t split because it can’t. The wavefunction of the photon captures the fact that the photon could be in two equally likely states (lower path and upper path). Then using this wavefunction you can calculate the probability that the photon is detected at D0 and D1 and you get:

| Photon outcome | probability |

|---|---|

| Detected at D0 | 1.0 |

| Detected at D1 | 0 |

But importantly, we cannot say whether the photon was in state TR (upper path) or RT (lower path) only that it was detected at D0. This is an example of particle-wave duality - the photon’s wavefunction acts like a wave (destructive and constructive interference), but is ultimately measured as a single photon.

WHY is Superposition

No one knows for sure and those that think they do can’t agree.

WHEN is Superposition

Although we don’t know why it happens, we can describe the conditions when we observe it. In this case, it happened because the observers (e.g. you, me, or the universe) couldn’t tell which path the photon took. Each path was sufficiently ambiguous to allow the photon’s wavefunction to remain in superposition. In Experiment 10, when we blocked the lower path, the photon couldn’t be in superposition because we knew it must have taken the upper path to arrive at the detectors.

Summary

Experiment 11 explored the wave-like nature of a photon demonstrated by the destructive interference that occurs between the two superposition states of the system. The next experiment explores what happens when we remove the second beam splitter.

Appendix: The Smalltalk code

The full Pharo package can be found at dlfeps/MZI.