Experiment 19

This post describes the stable diffusion architecture for generative AI.

Introduction

I am going to introduce this post with a real conversation I had with Microsoft’s Copilot:

Me:

Can you explain Generative AI to me like I am 5 years old?

Copilot:

Certainly! Imagine you have a magical drawing book. When you open it, it creates new pictures all by itself! That’s what generative AI does—it makes up things like drawings, stories, or even songs without anyone telling it exactly what to create. It’s like having a creative friend who invents cool stuff just by thinking about it! 🎨✨

Me:

Are you an example of a Generative AI?

Copilot:

Indeed! I’m like a friendly digital artist. When you ask me for something, I use my magical algorithms to create new sentences, poems, or even drawings. Just like a painter mixes colors to create beautiful pictures, I mix words and ideas to make interesting content! 🎨✨

Me:

Can you generate an image of an Eastern Bluebird drinking a milkshake?

Copilot:

END OF CONVERSATION

I was impressed by the generated images. Behind the scenes, Copilot uses an OpenAI product called DALLE-3 to generate images. Unfortunately DALLE-3 is not publicly available. So, for the remainder of this post, we will instead examine a closely related model called Stable Diffusion. How do they compare? Here is the output of Stable Diffusion for the same prompt above:

Generally Stable Diffusion tends to produce images that are more photorealistic whereas DALLE-3 creates images that feel like computer-generated art.

Unconditional Image Generation (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models)

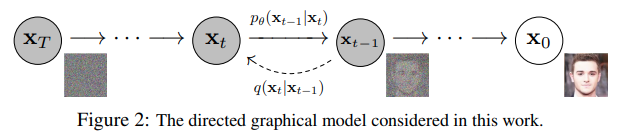

I will explain Stable Diffusion through a series of increasingly complex models. The first - and most foundational model - is the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM), which serves as the core technology behind Stable Diffusion and DALLE-3.

DDPMs are a class of generative models that work by iteratively denoising a diffusion process, which involves adding noise to an image and then trying to remove it. The underlying theory of DDPMs is based on the idea that transforming a simple distribution, such as a Gaussian, through a series of diffusion steps can result in a complex and expressive image data distribution. This allows the model to generate new images by reversing the diffusion process, starting from the full Gaussian distribution and ending up with the image distribution.

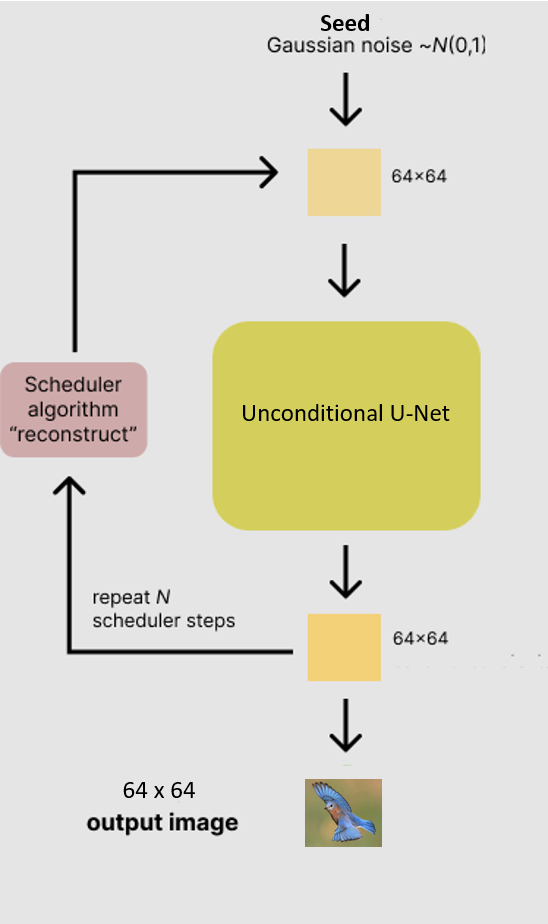

To further demonstrate the contribution of each step I will show what kind of generative images are possible using the CUB-2011 dataset. Our final goal will be to produce fully synthetic birds. In this first step we will only be able to generate small bird-like shapes using the DDPM architecture alone.

Figure adapted from https://huggingface.co/blog/stable_diffusion

The output of training the model is shown below. Here I take a snapshot of the sample images every 10 epochs to show the learning progression of the model.

You can see birds if you squint, but the low resolution (64x64) makes these images less useful. DDPMs top out around (256x256) and become increasingly slow to train on a single GPU. We next explore two options for increasing the resolution.

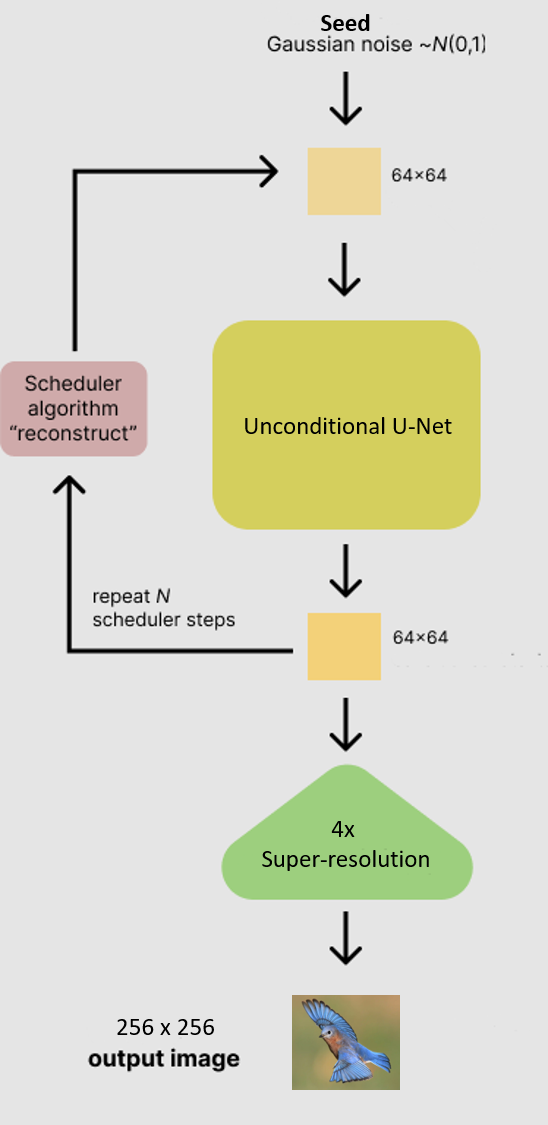

Generating Higher Resolution Images

The following two sections offer alternatives to increasing the resolution of the generated images.

Upscaling

The first approach uses image upscaling to increase the resolution of an image. Traditional upscaling methods, such as interpolation, don’t increase the inherent resolution of the image. The upscaler used here actually fills in missing details to increase resolution (NOTE: the upscaler itself is based on stable diffusion architecture). The architecture for the approach is outlined below:

Figure adapted from https://huggingface.co/blog/stable_diffusion

The benefit of this approach is that it uses the same DDPM from step 1 (which produces images of 64x64) and then the upscaler increases the resolution to 256x256.

The disadvantage of this approach is that the upscaler is not tuned specifically for your data (although it could be with additional training). It also makes a slow process (sampling the DDPM) even slower because you are performing two indepdenent steps (sampling then upscaling).

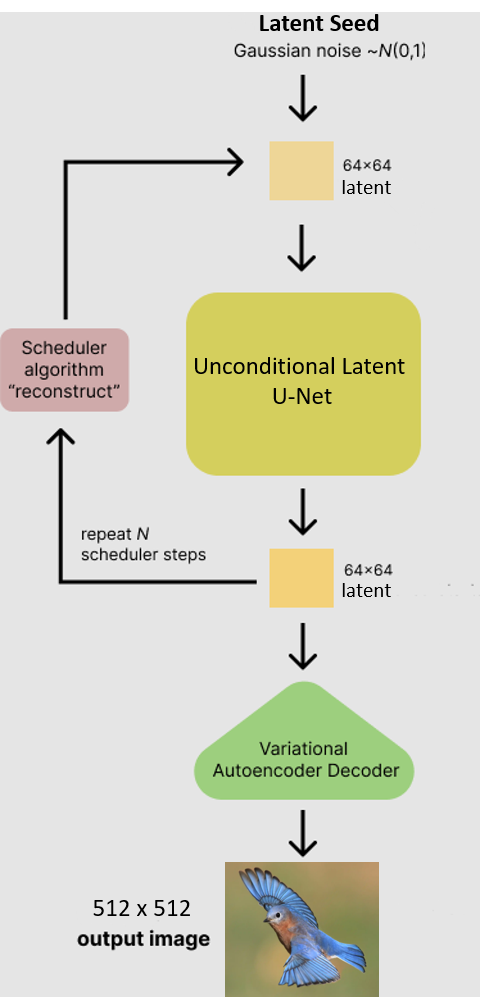

Latent model

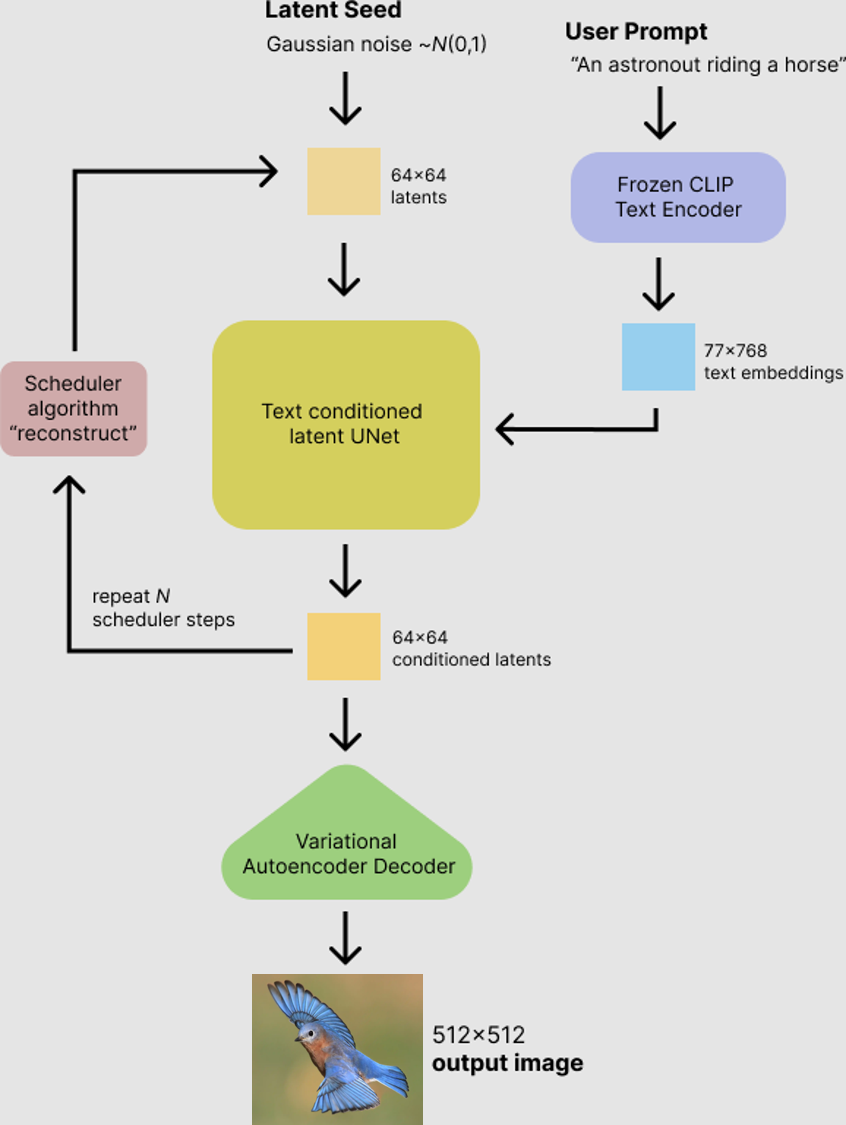

The second approach to increasing resolution was introduced in “High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models”. The idea behind this approach is to surround the DDPM with a pretrained variational autoencoder1. The DDPM then learns to denoise the latent space (which also happens to be 64x64) instead of the image space. To create a new sample:

1. generate random noise in the shape of the latent space

2. use the DDPM to denoise the input

3. use the decoder to transform the latent space back into image space (512x512)

Figure adapted from https://huggingface.co/blog/stable_diffusion

Unfortunately I did not have enough Colab credits to fully train this variant2. Although the model outputs images that are 512x512, I admit that they don’t look very bird-like. Here is a single full image created after 50 epochs of training:

Conditional Image Generation (Stable Diffusion)

Up to this point we have not had any control over what kind of bird gets synthesized. The final step is to condition the DDPM on another input (usually text, but it could also be another image). NOTE: In order to train such a model, the training data would require both text and captions. The CUB-2011 dataset does not provide captions and I also discovered that significantly more compute is needed to train the latent models so I will use a pretrained Stable Diffusion model.

Figure adapted from https://huggingface.co/blog/stable_diffusion

Here is an example output:

I generated the image above with the implementation provided by Lyumin Zhang called Fooocus. It is a pre-tuned version of StabilityAI’s Stable Diffusion XL model. You can generate your own images using the provided Colab notebook ->

Conclusion

Generative AI is currently experiencing a boom, with new research and products coming out every day. The code for this experiment can be found at my ML portfolio website. I would like to leave you with a final conversation from Microsoft’s Copilot:

Me:

Can you write a poem about generative ai?

Copilot:

Sure, I’d love to! Here’s a poem about generative AI:

In circuits deep, where data flows, A spark ignites, a thought that grows. From silicon dreams, a mind takes flight, Crafting worlds in the dead of night.

With algorithms as its guiding star, It reaches realms both near and far. From pixels bright to words that sing, Generative AI creates everything.

It learns from patterns, vast and wide, In every byte, where secrets hide. A painter’s brush, a poet’s pen, It brings to life what once was then.

Yet in its core, a humble start, A tool to aid the human heart. For in each line and crafted scene, It mirrors dreams, both bold and serene.

So here’s to code that dreams and dares, To generative AI, with whom we share, A future bright, where minds entwine, In harmony, both yours and mine.

END OF CONVERSATION

-

This particular autoencoder preserves spatial information by compressing a 512x512x3 image into a latent space of 64x64x4. ↩

-

As a comparison, in “High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models”, they trained a latent model on FFHQ for 283 hours on an A100. This would cost an equivalent of $370 in Colab compute units so you will have to forgive me for stopping early! ↩